RODNEY GRAHAM

Born 1949 in Vancouver, Canada. Lives and works in Vancouver.

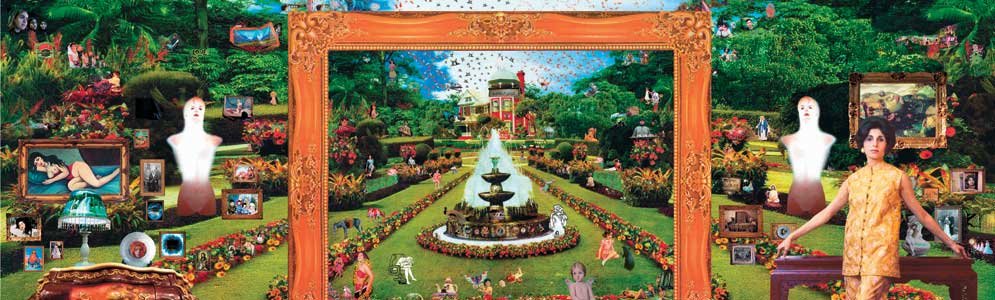

Rodney Graham, City Self / Country Self, 2000, 35mm film transferred to DVD, 4 mins looped. Courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery, London

Rodney Graham is one of the most influential and respected artists working today. His practice crosses the various media of painting, photography, video, performance, sculpture and installation. He is known for his intelligent, ironic and historically resonant works that excavate and re-imagine the history of modern art and culture and the artist’s place in it. Graham emerged out of a seminal group of Vancouver artists, including Jeff Wall and Stan Douglas, who were producing highly aestheticised works in photography and video that developed further levels of complexity, performance and play inherited from the conceptual artists of the 1960s and early 1970s. Graham’s work is textually dense and informed by historical, literary, musical, philosophical and popular references. His idiosyncratic practice also includes performing as a rock and country singer and songwriter (music being his first love). His quotations of country and western music are entirely sincere, as is his love of performance. There is a fascinating distance between Graham’s unabashed fondness for the traditions he enjoys and re-imagines and the cool, semi-ironic artworks that result from his passions.

Graham’s works re-investigate historical and literary texts, technologies and beliefs, often referring to psychoanalysis, literature and music. He is particularly interested in film as a historical medium and has used the structural technology of projection as an installation. Graham’s interest in early optical devices such as the camera obscura also influences his lightbox photographs that re-evaluate the early modern and post-Romantic perception of nature and human subjectivity. Graham’s video works are designed to loop endlessly – their cyclical, inescapable structure reveals an obsessive interest in repetition and compulsion.

One of Graham’s central concerns has been in the way nature and the interior world have and continue to be constructed in a Romantic fashion. He often places himself at the centre of his works, in some cases in the guise of an historical figure (real or invented) as a way of creating a personalised archaeology of Romantic modernism and the historical avant-garde. All of his work is concerned with the construction of different identities, particularly the three films which he regards as his ‘identity works’: Vexation Island (1997), How I Became a Ramblin’ Man (1999), and City Self/Country Self (2000).

In the two latter works, Graham inhabits a transitional space between town and country – a no man’s land that symbolises the impact of modernity in all its forms, including nationhood, the romance of the prairies, and European constructions of advanced ‘civilisation’. City Self/Country Self, shown in the 17th Biennale of Sydney, sees Graham take on the dual roles of an urban aesthete and country bumpkin. This film, set in the early part of the nineteenth century (presumably in England), shows an imaginary encounter between a dandy and a country yokel who comes to town. The yokel, confused and out of his element, represents the one who was there before (he could even be ‘an indigenous person’) and is summarily booted up the backside by the civilised gent. In a looping high comedy, Graham distils the self-legitimating impositions and defensive impulses that have marked the expansion of western thought and dominion over the modern centuries.

In How I Became a Ramblin’ Man, Graham enthusiastically adopts the persona of the loner, the traveller, the cowboy, the singer, riding across a bleak landscape and actually performing a song as part of the work. Yet this eulogy to the open road is not without a bitter after-taste. Hank Williams’s original song suggests a freedom and sense of authenticity long lost, if indeed it ever existed and, of course, the original ramblin’ men, upon whom the song is based, were trappers and outlaws, accepted by neither Indians nor settlers, living on the knife-edge of survival, who took what they found and tried to hold on to it.

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2010 ‘Rodney Graham. Through the Forest’, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Spain

2009 ‘HF|RG’, Jeu de Paume, Paris, France

2008 ‘A Glass of Beer’, Centro de Arte Contemporaneo De Malaga, Spain

2006 ‘Rodney Graham’, Musée d’Art Contemporain de Montréal, Montreal, Canada

2004–05 ‘Rodney Graham: A Little Thought’, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada (travelling exhibition)

Selected Group Exhibitions

2009 ‘Little Theatre of Gestures’, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Basel, Switzerland and Malmö Kunsthall, Malmo, Sweden

2008 ‘The Cinema Effect’, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, USA

2005 ‘Situation Comedy: Humor in Recent Art’, The Contemporary Museum, Honolulu (travelling exhibition)

2003 ‘C’est arrivé demain’, 7th Biennale de Lyon, Lyon, France

2002 ‘(The World May Be) Fantastic’, 13th Biennale of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

Selected Bibliography

Kim Gordon, ‘Rodney Graham’, Bomb magazine, no. 89, autumn 2004

Steven Harris, ‘Pataphysical Graham’, Tate Research, autumn 2006

Pernilla Holmes, ‘Ramblin’ Man’, Art News, March 2003, pp. 102–5

Pablo Lafuente, ‘Cross Platform: Sound in other media. This month: Rodney Graham reveals why strapping on a guitar is good for his art’, The Wire, no. 262, December 2005, pp. 78–79

Shepherd Steiner, ‘In the Studio with the Gifted Amateur’, Modern Painters, March 2007, pp. 64–69